When Two Tribes Go to War

The extremists on both sides of the political spectrum spend a lot of time trying to persuade everyone on their own side that everyone on the other side is an extremist. I believe those of us who are not extremists should fight back.

I’ve been learning about Anthony Smith’s concept of an ethnie in my class on Classical Greece and Rome. According to Smith, an ethnie is a named unit of population with ‘common ancestry myths and historical memories, elements of shared culture, some link with a historic territory and some measure of solidarity’. Smith distinguishes ethnies from nation-states (which share territory) and ethnic groups (which have distinct physical features). Let’s look at the ethnie of the Greeks.

The Greeks of classical times were spread all over the Mediterranean and did not share land or administrative leadership — so they were not really a nation. And they were not physically different from their neighbours so they were not an ethnic group either. However, according to Smith’s criteria, the Greeks constituted an ethnie because they shared:

- A common name: The Greeks.

- Ancestral myths: They believed they were descended from the heroes of the Iliad.

- Historical memories: The Persian and Peloponnesian Wars.

- Cultural distinctiveness: They spoke the same language, built similar temples and carved similar statues.

- A homeland: Although the Greeks were spread all around the Mediterranean, they had a shared memory of the land that they came from.

- Solidarity: They worshipped the same gods and had similar laws and conventions.

Smith’s criteria are handy for lumping together the people who we call Greeks and distinguishing them from the people who were not Greeks. This made me wonder whether we can apply the same criteria to the people who we call The English and distinguish The English from other ethnies.

I’ll come back to this after a quick aside about populism.

The Old Elite

If you’ve read any commentary about Brexit or the Trump phenomenon in recent years, you’ll have noticed that populist commentators on the right place a lot of blame on a group that they refer to as the elite.

We’ve always had elites of course. In years past, we had an aristocracy with people like Lord Rothermere or Baron Rees-Mogg. In the old days, elites went to schools like Eton and Winchester and universities like Oxford and Cambridge. They dominated the government, the media and the civil service and they had vast wealth, owned great estates and controlled the corporations. The USA had a similar elite but their plutocrats went to Harvard and Yale and wrote for the New York Times. They dominated the Senate and the Supreme Court and they vacationed in the Hamptons.

This old-school elite still exists of course but, according to the conservative commentators that I read, there is a new elite that is taking their place in the corridors of power. This new elite still goes to Oxbridge and the Ivy League. They still run the media and the civil service and they still control the corporations. But where the old elite used to treat ordinary people with respect (ha!), the new elite look down on them with disdain. The new elite’s priorities are no longer aligned with the rest of the country’s in the way that the old elite’s were and this has resulted in social division, disgust and disillusionment in the folks left behind. The consequences of all this unrest were a vote for Brexit and the election of a malevolent conman as President of the United States of America.

Note that a similar argument is often used to explain Les Gilets Jaunes and the election of populists like the Brothers of Italy, Alternative for Germany and Viktor Orban but I will focus on England and the USA as the two polities that I understand best. I’ll gloss over the obvious nonsense that the old elite treated the working class with respect, that their priorities were aligned with working people’s or that the old elite has gone away.

Politicians on the right — in both England and America — are fond of blaming the ills of the 21st century on this new elite but I’ve had trouble discerning 1) what makes the new elite so different from the old elite and 2) why the new elite are so pernicious.

I decided some research was in order and I started with Matthew Goodwin’s book Values, Voice and Virtue: The New British Politics.

Goodwin, too, blames the ills of the 21st century on the new elite and their contempt for the non-elite. According to Goodwin, most people in the old elite felt a strong sense of duty, patriotism, attachment and obligation to the majority group, loyalty to the institutions, and an instinctive desire to defend and uphold Britain’s national identity, culture and ways of life. But the new elite rarely feel any of these things

When Goodwin names his elite, he calls out the people who have been to university and now have good jobs in urban environments. They have influence in government, the media and commercial organisations and there seem to be a lot of them — more than there used to be, anyway. They seem to have a knack for passing their good fortune down to their offspring.

But wasn’t that ever the case? The main difference seems to be that more people are finding success than in days past so the people who are struggling feel it more keenly. Eliteness used to be restricted to people who went to Eton, Winchester and Dulwich College but now that eliteness is available to ordinary people who are smart and work hard, it represents a threat to our nation.

When Goodwin talks about elites, I think he means me but the more I read, the less sure I am.

I have been quite successful in my life. I’ve lived in four countries. I’ve worked on Wall Street and in Silicon Valley. I currently live in a neighbourhood in Bristol that Goodwin specifically calls out as elite and I previously lived on the waterfront in Manhattan.

I made it from the bottom quintile to the top quintile. I have respect for people of different ethnicities and sexual preferences. My children were born within wedlock and I am still married after 31 years. My daughter just completed her Master’s at a Russell Group university. All but maybe three of my friends are liberals. These are all attributes that qualify me as elite according to Goodwin. I’m one of the people that Theresa May called ‘The Citizens of Nowhere’.

I expect Goodwin would put me down as elite along with most of my friends, colleagues and neighbours. And yet, when I read his descriptions of the not-elite, I see myself there as well.

I grew up on a council estate. My parents divorced when I was 10. My dad worked in a meat factory. My brother works on a building site. I never went to university. I left home at 16 to do an apprenticeship. I served in the military. I love my country. Same deal with most of my friends, colleagues and neighbours.

There must be something else that is dividing us elites from the non-elites because the characteristics that Goodwin lists miss the target.

Goodwin says that the not-elite voted for Brexit and Trump because of the contempt that the elite had for them but I think he has the cause and effect exactly backwards. Speaking for myself, I never had contempt for people who work manual jobs or who missed out on a degree — I don’t have a degree myself — but I am somewhat irritated by the people who took away my opportunity to live and work in Europe and made it so difficult for my wife and children to remain in this country. If they messed up my life because they were angry at me for being successful, I think it’s worth trying to understand why. I’ve come to believe the elite label is a red herring and a mischievous one at that.

I think the real problem is our changing conception of ourselves as English people — our understanding of our ethnie.

The new ethnie

In the past, it was mostly rich people who went to university or, at least, people with a family history of going to university. If you grew up working class back then, it was rare even to know someone with a degree. The only people I knew with degrees were my teachers and my doctors, and I never even spoke with any of them. In my extended family, I had a single uncle-by-marriage and one cousin who went to university. We thought of them as incredibly posh.

When my older sister got good A-level results, she asked my parents if she could go to university and they told her “We think you’ve had enough schooling now. It’s time to go and work for a living.” I didn’t even give them a chance to say “no” to me and I quit school at 16, after my O-levels.

Back then, it was possible to be successful without a degree. One sister got a job with an insurance company; the other at a bank. My brother and I got apprenticeships. By the time I was 21, I was a successful engineer earning more than my dad.

These jobs are no longer available because of our country’s obsession with sending everyone to university. We’ve made it easier to get a degree but we’ve made it harder to be successful for everyone who chooses a different route. It’s no wonder they are resentful.

The culture is changing too. Folks who go to university tend to be cosmopolitan. They are more likely to move to the Big City when they graduate and they are more likely to know people from other cultures — from Nigeria or Spain or Bangladesh — and more likely to have a friend who is gay or trans.

Folks who have been to university are more relaxed about immigration too. and they are more friendly with the nice Polish family who live next door. They are less likely to be upset by a request to state their pronouns or by the leg-up offered to ethnic minorities who have historically struggled on the way to academia.

It’s no wonder that folks who don’t enjoy these new cultural elements are disoriented and it doesn’t help when the message from the media is that dissatisfaction with immigration is racist or that annoyance over pronoun declarations is transphobic.

Evolving rules and conventions

So there are cultural differences between the new ethnie and the old ethnie. We are also seeing changes to the moral rules and conventions that we are expected to follow.

Commentators like Goodwin would have us believe that liberals have rejected the cultural habits of the past but, actually, liberals are more likely to get married and stay married and to have children within marriage than conservatives in both the UK and the USA. This is a perfect example of conservative commentators accusing liberals of the sins that everyone except liberals commits.

Demographers Jennifer Glass at the University of Texas and Philip Levchak at the University of Iowa looked at the entire map of the United States and one of the strongest factors predicting divorce rates (per 1000 married couples) is the concentration of conservative or evangelical Protestants in that county.

But there are other cultural sins where the reality of cultural change is more problematic.

Mixed-gender toilets are disorienting, for example. It’s one thing for men and women to use the same toilet in a small café but it’s another thing entirely to stand in line with 20 women to use the toilets at the cinema — making eye contact with the women washing their hands is especially awkward. How will it feel when it’s 20 men and one woman in the toilet late at night? In single-gender toilets, men are in and out quickly. In mixed-gender toilets, men have to stand in line for ages and then they piss all over the seats that the women have to sit on. The whole mixed-gender-toilet thing feels like a symbolic gesture that creates more problems than it solves.

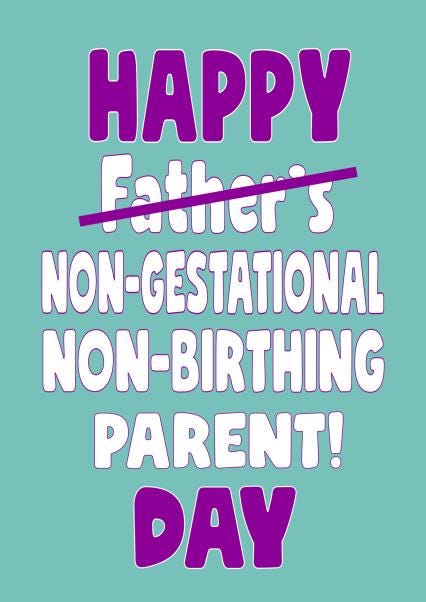

There’s an argument that we can get used to cultural rule changes like this one but when the changes come in quick succession, they are disorienting and it feels like the ethnie you belong to is under attack. Throw in changes to the language like chestfeeding and speaking of mothers as birthing parents and is it any wonder that people used to the old ways get annoyed? What are the problems that these changes are intended to solve anyway?

I could list many cultural changes like these but I think what makes them especially bothersome is the sense that you will be severely punished if you violate the new rules even if you don’t know what the rules are.

“Going to Africa. Hope I don’t get Aids. Just kidding. I’m white!”

– Justin Sacco

Justine Sacco’s life was destroyed when she made a stupid joke on Twitter. The joke itself was meant to be self-deprecating — a kind of satirical comment on racism in the way that Alf Garnet in ‘Til Death Do Do Us Part (Archie Bunker in All in the Family in the USA) made fun of racists. Maybe jokes like that aren’t allowed any more and maybe it’s time to move on. But where we used to suffer 15 minutes of criticism for a stupid joke, the penalty now is that you become internationally (in)famous, you lose your job and no one will employ you ever again.

Or maybe the police will show up at your door.

Harry Miller, received a visit from the Humberside police and was told that his tweeting was being recorded as a “hate incident” for this tweet:

“I was assigned Mammal at Birth, but my orientation is Fish. Don’t mis species me.”

Again, it’s not just the changing culture that causes stress. It’s the fact that you can suffer outrageous penalties for violating cultural rules that you barely knew existed.

The FA chairman, Gregg Clarke was forced to resign when he referred to ‘coloured footballers’. In the irony of ironies, this was during a discussion intended to reduce the level of abuse faced by minorities. Clarke said: “If I look at what happens to high profile female footballers, high profile coloured footballers and the abuse they take on social media … they take absolutely terrible abuse.”

In a sensible world, someone would have said to him, “Now then, Gregg. We are not allowed to say ‘coloured people’ any more. We are supposed to say ‘people of colour’”, Clarke would have learned his lesson and it would have been all over. Instead, a man’s career was destroyed.

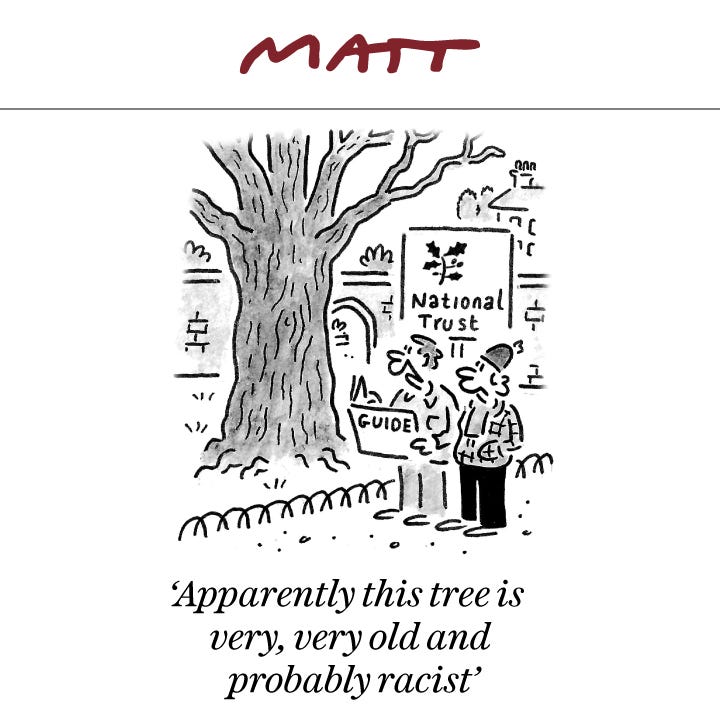

Of course, it’s not just my side that wields the Cancel Culture axe. The right is very quick to swing it too and conservative politicians ban books they don’t like in schools, demonize people who support drag shows and lead boycotts against beer companies.

I believe moderates have a duty to criticise their own side when extremists ruin people’s lives for a minor infraction of the ever-changing social codes. Instead, they keep quiet or just go along for the ride.

Immigration is a problem

People have a habit of pretending that the extremists on the other side of the political fence are typical of that side. On my side — I’m on the left — some people really do believe that everyone who opposes immigration is a racist. Some progressives believe that the only reason to be concerned about 150,000 asylum seekers arriving in boats is racism but, actually, it’s a problem that needs to be solved. In 2021, over one and a half million immigrants arrived from India and Pakistan. This is a problem too and it has very little to do with racism.

I frequently read right-leaning commentators pretending that the elite on the left celebrates high levels of immigration because it gives them more power over the white working-class people who oppose their agenda — but that’s just nonsense. The Guardian (the leftiest of lefty newspapers) has an article today — What the unrest in Leicester revealed about Britain — describing how religious tension between Muslim and Hindu immigrants is a problem. Plenty of cosmopolitan elites agree that immigration is a problem, despite what the political mischief-makers say.

For sure, we cosmopolitans believe that immigrants should be treated with respect but it’s a lie to say that because we want to treat immigrants with respect we support higher levels of immigration. For sure, some people want higher levels of immigration — the industrialists who donate to the Tory party, for instance — but it’s just untrue to say that most liberals are in favour of it. It should be possible to believe that immigration is too high but, while we do need to solve the asylum problem, we believe that shipping people off to Rwanda is performative cruelty that should have no place in a civilised country.

Can’t we solve these problems together?

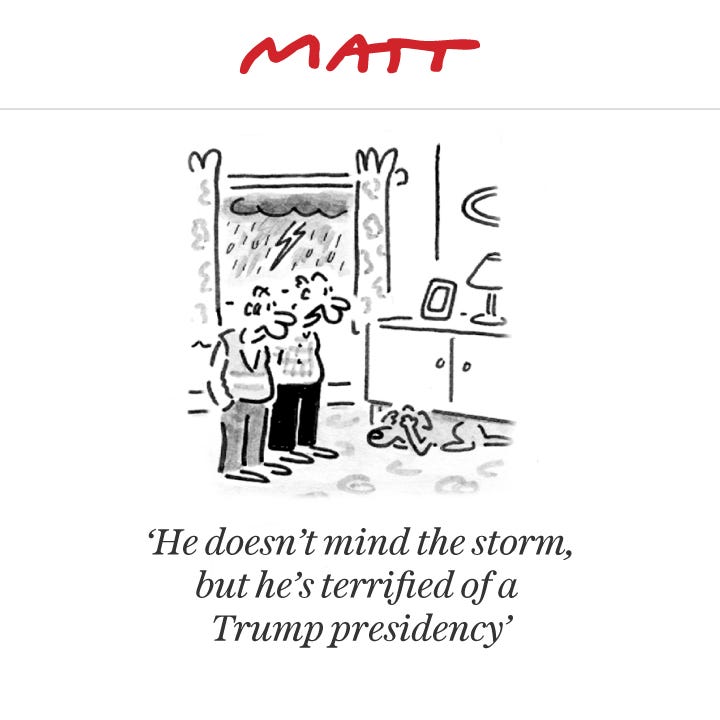

If you listen to the commentators, in both the UK and in the USA, you’d think we are dividing into two ethnies. One lot wants to swamp the country with immigrants and tear up the books that celebrate our history. The other side wants to ship all the immigrants off to Africa and ban gay weddings.

There’s a phenomenon in the culture wars where the extremists on one side REALLY CARES about a problem and while most other people disagree, they don’t care enough to do anything about it… until the extremists get their way. And then the resulting backlash makes everyone unhappy. The extremists get all the headlines and everyone else quietly seethes… and before you know it, people are voting for an Orange Proto-Fascist for President or, worse, Brexit and we all suffer.

Much better, I think, to criticise your own side when they do stupid stuff. Firstly, we’ll stop the extremists from doing extreme stuff. Surely we can all agree on that one. Secondly, we’ll be able to make common cause with the moderate people on the other side and maybe they’ll stop accusing us of extremism. And maybe they’ll stop voting for lunatics.