I, my self.

I attended a meeting of the marvellous Café Philo this week. The topic was “What does it mean to be you?” I got frustrated, at times, that everyone had their own definition of what was meant by the self. I thought I’d take a shot at a definition that everyone can agree with.

Some meanings of self that I picked out on Monday:

- The self is our core identity. It is who we are (see also: identity).

- The self is the bit that does the thinking (see also: mind).

- The self is the bit that will be judged on Judgement Day (see also: soul).

- The self is how we present ourselves to those around us (see also: character).

- The self is the part that doesn’t change. It’s with us throughout our life (see also: person).

I think there is a simpler, commonsense definition of self.

My self is the collection of body parts that are me. I have a left foot, a heart, two eyes and a nose (and some other bits). Those body parts constitute my self.

You have your own parts that constitute your self too. My foot is part of my self. Your foot is not. Neither is my chair. If I lose my leg in an accident, it will no longer be part of my self. If I get an artificial leg it will eventually (fingers crossed) become part of my self.

Even primitive organisms like amoebas can distinguish between this bit is me and this bit is not me. We higher animals have systems, like our immune system, that detect and evict foreign (not-me) invaders. Higher animals may have a more sophisticated understanding of their self than amoebas but even primitive animals know not to eat their own bits.

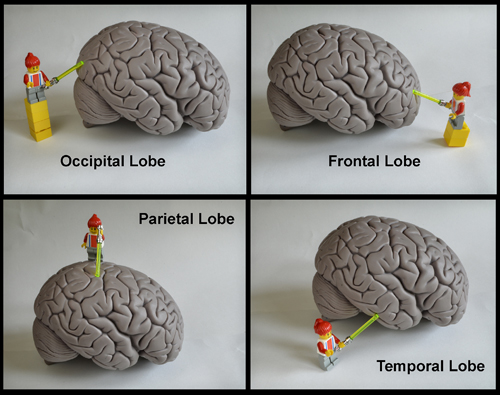

There is a bit of my brain—my insula—that builds an internal model of my self. It takes all of the inputs of my senses as well as the position and movement of my limbs and decides which bits are me and which bits are not me. If the insula is damaged—because of an injury or a tumour, for example—my model of my self might have errors. People who lose a limb sometimes suffer from phantom limb syndrome where they imagine that the lost limb is still there. Conversely, sometimes we don’t recognise the thoughts in our head as our own thoughts and imagine that someone else is speaking to us or controlling us.

We can also be tricked into thinking that a bit that is not ours is ours. The Rubber Hand Illusion tricks us into thinking that a rubber hand is actually our hand.

So here we have a useful distinction: our self and our model of our self are not necessarily the same. What about those other concepts that people confuse with the self?

John Locke (1632-1704) seems to use self, soul and consciousness interchangeably. For Locke, the self (and soul and consciousness) is the bit that does the thinking. For me, my brain is the bit that does the thinking.

What about the mind? How is that different from my brain?

My mind is the activity in my brain. A clock ticks as it tracks the passage of time but the time is not the clock and the ticking is not the clock even though the ticking cannot be separated from the clock. In a similar way, my mind cannot be separated from my brain. It is what my brain does. My mind includes the sum of my thoughts but it is my brain that does the thinking just as a clock does the ticking. And my mind is not my self. Mind and self are different things.

How about the soul? I have always dismissed the soul as a supernatural thing but a philosophical friend persuaded me that there is a pragmatic, natural understanding of soul that doesn’t require supernatural thinking.

The soul is the pattern of chemical and electrical activity that begins at conception and ends at death. As long as that pattern of activity continues, we are alive. When it stops, we are dead and the soul is gone.

My friend says that this was the understanding of the soul throughout the Old Testament and it was St. Paul’s understanding too. It wasn’t until much later that Christians tried to blend Greek ideas of the psyche and pneuma with Jewish ideas of the soul that people started to think of the soul as an immortal substance, implanted by God, that survives the death of the body (Locke thought the soul would be judged on the day of judgement). Either way, soul and self are different things.

One idea that came up a lot on Monday was that one’s self changes over a lifetime, by which they mean how one sees one’s self and how one behaves around other people. I think how we see ourselves is our personal identity and how we behave is our character or, perhaps, our personality.

If you see yourself as strong, smart, trustworthy, brave and kind, those are attributes of your character not your self. Your personal identity might be defined by your gender, your nationality or your profession but, again, that’s different from your self.

Identity is a tricky word though. If two things are identical, they are the same. Philosophy makes a distinction between qualitative identity (these items are the same) and numerical identity (these are the same item). Personal identity in everyday speech is about how you see yourself (I identify as a man) while in philosophy, it is about whether you are the same person you were last week or last year.

Have you heard of the Ship of Theseus? If you have a ship and you change the sails, it’s still the same ship. If you change all the sails and all the masts and all the planks, is it still the same ship? If a man shaves off his beard, is he still the same man? The shaved man is no longer identical to the man with the beard but I am sure we’d agree that he is the same man and he doesn’t become a different man if he gains a few wrinkles or forgets his childhood.

What if you replace all the planks and use the planks to build a new ship?

John Locke made a distinction between a person and a man. A man who shaves off his beard is the same man but a person who loses his memories is no longer the same person. What is a person, actually? How is it different from a man? For Locke, your person is about keeping track of who is to blame for an action or who deserves a reward. If someone has forgotten that they murdered thousands of Jews in the Holocaust, they are no longer the same person and therefore no longer to blame for it. I don’t find the distinction between a man and a person useful though, regardless of implausible thought experiments about mind-swapping and teleporters. As long as my pattern of life activity continues, I am the same person. It gets a bit confusing with the possibility of heart transplants and kidney transplants though, so let’s say that it’s the continuity of activity in my brain that determines whether I’m the same person, even if I’ve forgotten earning my Twenty-Five Yard Swimming Badge in the third year juniors. But, in any case, personal identity is not the same thing as the self.

Lots of folks carry around mediaeval or early modern understandings of the self that bring confusion to the discussion rather than light and it reminds me of the old joke.

How do you get to Dublin?

Well, I wouldn’t start from here.

We have a much better understanding of biology and neuroscience in the twenty-first century than John Locke had in the seventeenth. If you want to understand the self, I’d start from this century.