My Deepest Shame

Roger Ebert has written a powerful, meandering essay about shame.

The essay takes many twists and turns and each one of them is a fascinating journey in its own right.

It starts out as a review of the movie The Reader.

I was watching Tony Scott on the Charlie Rose program, and he said, in connection with “The Reader,” that he was getting tired of so many movies about the Holocaust. I didn’t agree or disagree. What I thought was, “The Reader” isn’t about the Holocaust. It’s about not speaking when you know you should.

[It’s great that The Reader is not about the holocaust because I’d like to see it and my wife wouldn’t watch it with me if it were about the holocaust.]

In his first meander, Ebert uses Twain

That wise man Mark Twain told us: “In religion and politics people’s beliefs and convictions are in almost every case gotten at second-hand, and without examination, from authorities who have not themselves examined the questions at issue but have taken them at second-hand from others.”

as an excuse to reel off a laundry list of Things He Believes

This is true. It is even sometimes true of me. Perhaps of you. However, there are certain areas in which I consider myself an authority, like the movies. I have devoted years to learning about the Theory of Evolution. I think Creationism is superstitious poppycock. I believe the problem with the literal interpretation of the Bible is that anyone can easily discover its support for the opinions they already hold. I believe Conservatism has proven itself disastrous every time it has been implemented in this country.

After meandering past speaking engagements, dinner parties, segregation and atheism – with every meander a gem – he ends up back at The Reader.

The Reader, Ebert says, [Spoiler Alert!] is about a woman’s wrongful conviction that she could have easily avoided if only she could overcome her shame about her inability to read. A key witness realizes this but fails to speak up because of his own shame that he had an affair with her.

This is where his essay gets interesting because it leads Ebert into a riff on the power of shame

We learn of young mothers who put their babies in dumpsters because they are ashamed of their pregnancy. Young fathers who murder their girlfriends, simply because of the universal human reality of pregnancy. We hear of prison guards who follow orders to torture, orders they know are illegal and immoral. And leaders who issue the orders. We learn of terrorists who die and kill others rather than face the shame of being frightened to. We hear of gang members who kill people unknown to them, not because they want to, but because they have been shamed into “proving” themselves as men. We hear of Wall Street executives who lead their firms into what they know are dangerous and unsound practices, because they would be shamed to be outdone by rival executives. They steal the savings from millions of victims, so they can win a pissing contest.

and ultimately triggers Ebert’s memory of a shameful episode in his own past. Ebert’s shame story is about cheating in a game of chess with a blind man who was his very good friend.

More than 40 years have passed since that game, but I have not forgotten it. I can never even think of the University of Cape Town without it coming to mind. My cheating itself was shameful. When I denied it, that was despicable. Herb, I hope someone reads this and tells you about it. You were right. Of course, you always knew you were right, and we both knew that I had lied.

Just reading that makes me feel that familiar burning sensation that heralds the unbidden return of my least favourite memory. Suddenly I am transported back to my fourth-year Latin exam in Room 41 and

David Samuel is handing me his exercise book under the desk.

We are halfway through our end of year exams.

Our exams are kind of a big deal because, unlike America in 2009, in England circa 1981 the only thing we will have to show for all our years of schooling is a certificate that said how we performed in a bunch of exams — O Levels — that we’ll take at the end of the fifth year (aged 16).

We do two of these three hour exams for each O Level (plus an oral exam for languages). I’m taking 9: English, English, Maths, Maths, Chemistry, Physics, Biology, French and Latin.

Every year until now has ended with a solid battery of two weeks of exams with 8 hours a day under exam conditions. Our grades throughout the year are based on classwork and homework but all that was tossed aside after the exams. Only the exam counts. The fourth year exams are special because they are a dress rehearsal for the real thing at the end of the fifth year.

For me, exams are a godsend. The laziest student ever (until I have children of my own), I have made avoiding work into an art-form. In the last two years of chemistry, I have written a total of three and a half pages of notes and have done no homework at all. I read computer magazines in Latin class and I am teaching myself BASIC in French. I am bottom of my class. In two weeks I will be top of my class. Again. They stopped giving me Most Improved Student Award after four years of improving from worst in class to best in class every exam time.

Best of all, I genuinely enjoy exam time. We have no homework assigned and I have no need to study. The fact that I have no notes to study from is irrelevant. I will not open a book. Last Christmas, Miss Mills said that we should be studying about 6 hours a day by now. I have not studied for 6 hours total in my whole life and Not At All for these exams.

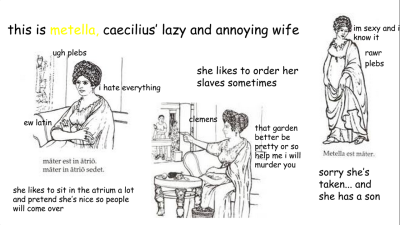

Each subject has two exams: one essay-based; one short answers. In Latin, the second exam requires us to translate passages of Latin.

In class, we have translated Caesar’s Gallic Wars, Tacitus’ Histories, umpteen poems by each of Ovid, Horace and Catullus and the complete works of Pliny the Younger. In the exam, we’ll have to translate some 10 or 12 of these.

And now I’m sitting in the back row of room 41, next to David Samuel and, when I open the exam paper, I realize that I don’t know anything.

It’s easy to fake your way through translating French. It’s all “Ou est la Place de la Concorde” but Latin is much more precise, more distant. More foreign. And you certainly can’t fake your way through poetry. They expect us to understand it.

David Samuel leans over, opens his bag and shows me that he has a book with all the translations. “Give it to me”, I signal. He smiles and hands it over. I copy just enough to save me from being booted out of Latin class because Mr Hickey doesn’t want bad students sullying his class’s record.

That feeling of dread when I opened the exam paper inspired me to study for an exam for the first time in my life.

I still didn’t study for Maths or any of the sciences because they were easy (all As, in case you are wondering). Nor English Lang because: what’s the point? Neither did I study for English Lit as I had never got better than 8% and studying wasn’t going to make much difference.

[I didn’t even read one of the assigned books – Brighton Rock – until I was 23. When I did finally read it, I fell in love with Graham Greene and have now read all of his books. If I had read it at 15 like I was supposed to, I might’ve gotten a better grade at ‘O’ Level but I might’ve hated Greene and never read him again.]

But I did study Latin.

I memorized the translations of every single one of those histories, poems, legal documents and letters to Emperor Trajan except Pliny X.96 — the one about the Christians — but that’s a story for a different day.

I still remember many of them by heart now.

That Suffenus, whom we know well Varus,

Is a charming, witty and sophisticated man.

Yet at the same time he writes more verse than anyone else.Not, as usually happens, on second class papyrus.

He uses new papyrus, all ruled with lead and smoothed with pumice…

But, more than the poems, I remember the shame because it eats into my conception of who I am. I have barely spoken with David Samuel since that day but I don’t think I could even look him in the eye if I saw him again.

Worse still, he was the boyfriend (and eventually married) my girlfriend’s best friend. I imagine him telling Sarah who tells Jo: Remember Kevin? The kid who was good at exams? He was a cheat. I saw him. He used to take books into the exams.

David Samuel’s mum used to work with my mum. They were very competitive about their offspring as mothers often are. What if David’s mum knows I am a cheat?

I never cheated again but that once was enough to give me a lifetime of shame.

The common element of all these shame stories leads me to propose the following hypothesis:

Our greatest shame arises when we do something that is not just bad but that conflicts with our image of ourselves.

Ebert’s is bleaker:

I believe the movie may be demonstrating a fact of human nature: Most people, most of the time, all over the world, choose to go along. We vote with the tribe. What would we have done during the rise of Hitler? If we had been Jews, we would have fled or been killed. But what if we were one of the rest of the Germans?

It’s a shame that the movie is about the holocaust because I’d really like to go see it but my normal movie-going companion won’t take me so it will be condemned to my Netflix queue where it will fester until it finally arrives and sits on the shelf for three weeks because I can only watch those movies after everyone else has gone to bed which seems to get later and later as the years go by.

It’s a shame, I tell you.