Mysterious God

In the newspaper that Americans like to call The Times of London, my favourite Rabbi writes a rather thoughtful article about how The Argument from Design was never a very good argument anyway. So, while Darwin’s marvellous idea may have dealt a death blow to believers in a literal creation, thoughtful believers, like Britain’s Chief Rabbi, who think of those first verses of Genesis as allegorical had nothing to wonder about.

The Rabbi’s belief is founded on the mysteries that are safe from science’s searching eye.

In fact none of the most important truths can be proved: that right is sovereign over might, that it is better to be loved than feared, that every human being however poor or powerless is worthy of respect, that peace is nobler than war, forgiveness greater than revenge, and hope a higher virtue than resignation to blind fate. Lives have been lived and civilisations built in defiance of these truths, yet they remain true.

The believer might mention other mysteries, such as how did life evolve from non-life? How did sentience emerge? How was the uniquely human capacity for self-consciousness born? How did life evolve at such speed that even Francis Crick, co-discoverer of DNA, was forced to suggest that it came from Mars? And the ultimate ontological question: why is there something rather than nothing?

We might refer to the arguments that persuaded the philosopher Antony Flew, late in life, to abandon his atheism. She might cite the curious paradox, noted by Richard Dawkins, that selfish genes get together and produce selfless people. We might wonder at the fact that Homo sapiens is the only known life form in the Universe capable of asking “Why?†And we might add, in the spirit of Godel’s Theorem, that there are truths within the system that cannot be proved within the system.

We would then say: None of these is a proof. Each, rather, is a source of wonder. The Psalm does not say, “The heavens prove the existence of Godâ€. It says, “The heavens declare the glory of Godâ€. Darwin helped us to understand how the many emerged from one. The more we know about the intricacy and improbability of life, the more reason we have to wonder and give thanks.

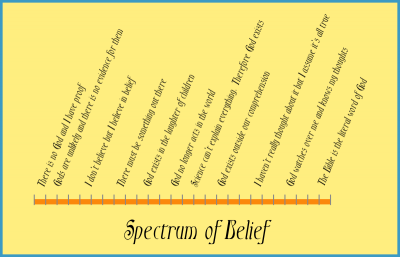

On the spectrum of belief, this falls somewhere between Science can’t explain everything and God exists outside our comprehension.

I know, from reading Sack’s previous writings, that his God is the mysterious God that exists outside of our understanding and that’s the God that I am most interested in. It’s all too easy to dismiss the other Gods but this God is more powerful than the others because it does not really exist according to our usual understanding of ‘exist’. If the Koran had a name for it it would be The Undismissable One.

I enjoy a good paradox and I wish I understood what it means to believe in something that does not exist. I also wish I understood how Jonathon Sacks squares this belief with the stories in the Old Testament. [I wonder if Johnathon Sacks has a Google Alert on his name like Alan Kay has? (Hi, Alan!)]

In my Slippery Trinity, I called this kind of God The Mysterious God. PZ Myers calls it “Oom“.

Theologians play that one like a harp, though, turning it into a useful strategem. Toss the attractive, personal, loving or vengeful anthropomorphic tribal god to the hoi-polloi to keep them happy, no matter how ridiculous the idea is and how quickly it fails on casual inspection, while holding the abstract, useless, lofty god in reserve to lob at the uppity atheists when they dare to raise questions…It gets annoying. We need two names for these two concepts, I think. How about just plain “God” for the personal, loving, being that most Christians believe in, and “Oom” for the bloodless, fuzzy, impersonal abstraction of the theologians? Not that the theologians will ever go along with it; the last thing they want made obvious is the fact that they’re studying a completely different god from the creature most of the culture is worshipping.