Flamboyant Genius – a little bit flawed – never in a modest mood

When I said that Crick was a flawed, flamboyant genius, I was guessing really. Pretty good guess, it turns out, as Matt Ridley’s fascinating mini-biography makes vividly clear.

Let’s get the flaws out of the way first. What I had in mind first time around was his total disdain for the institutions of religion and monarchy but, on reflection, I think he really deserves respect for standing up for what he believed in at potentially great cost to his career.

There are a bunch of interesting anecodotes about his antipathy to organized religion—Crick makes Richard Dawkins look like the Archbishop of Canterbury—but my favourite episode occurred when Crick was offered a founding fellowship of Churchill College. The college was being founded in honour of Winston Churchill as a specifically scientific college in an attempt to imitate the success of MIT. Crick had initially refused the fellowship because the college planned to add a chapel (the initial plan did not include one) and Crick thought a chapel had no place in a place of science. He was persuaded to change his mind because it was considered unlikely that the college would ever raise the funds to build the chapel. Crick became a fellow.

Shortly after that, one Timothy Beaumont donated the entire cost of the chapel and the foundations were dug before the fellows even got to have a say. Crick resigned immediately and sent a letter of resignation to Winston Churchill. He received the following reply:

I was sorry to learn that you have resigned from Churchill College, and am puzzled by your reason. The money for the chapel was provided specifically for that purpose by Mr Beaumont and not taken from general college funds. A chapel, whatever one’s views on religion, is an amenity which many of those who live in the College may enjoy, and none need enter it unless they wish.

Crick sent this reply:

To make my position a little clearer I enclose a cheque for ten guineas to open the Churchill College Hetairae [courtesans] fund. My hope is that it will eventually be possible to build permanent accommodation within the College, to house a carefully chosen collection of young ladies in the charge of a suitable Madam who, once the institution has become traditional, will doubtless be provided, without offense, with dining rights at the High Table.

Such a building will, I feel confident, be an amenity which many who live in Cambridge will enjoy very much, and yet the institution need not be compulsory and none need enter it unless they wish. Moreover it would be open (conscience permitting) not merely to members of the Church of England, but also to Catholics, Non-Conformists, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Zen Buddhists and even atheists and agnostics such as myself.

The trustees may feel my offer of ten guineas to be a joke in rather poor taste. But that is exactly my view of the proposal of the Trustees to build a chapel, after the middle of the 20th century, in a new college and in particular one with a special emphasis on science. Naturally some members of the college will be Christian, at least for the next decade or so, but I do not see why the college should tacitly endorse their beliefs by providing them with special facilities. The churches in town, it has been said, are half-empty. Let them go there. It will be no further than they have to go for their lectures.

Even a joke in poor taste can be enjoyed, but I regret that my enjoyment of it has entailed my resignation from the college, which bears your illustrious name.

The chapel was eventually built outside of college grounds.

Crick refused to attend weddings, funerals and baptisms in church but suggested that, if humanism were to take off it would need its own rituals, anticipating Kev and Jeff’s House of Death by 40 years. I think Francis Crick would have appreciated a sad, silent clown.

There is another great story which has a broke, father-of-three, Francis Crick writing to Jim Watson to request—and being refused—Watson’s blessing for a show about the double helix on BBC Radio:

Do you still feel you can’t allow the Third Programme Broadcast? I’ve yet to find anyone who would object to it, and things have cooled down a bit now. Also, it would bring in $50 to $100 which at the moment I could do with.

Watson refused his blessing:

If you need the money that bad, go ahead. Needless to say, I should not think any higher of you and shall have good reason to avoid any further collaboration with you.

Crick graciously declined to do the broadcast but this episode was perhaps in the back of his mind when he and Watson had their great falling out over the latter’s The Double Helix (Amazon, here I come again). Crick did everything he could to try to suppress Watson’s book which (I am told…still waiting for delivery) is written as much as a warts-and-all autobiography as an account of the science that led to the breakthroughs with DNA that won them their Nobel Prize. Crick succeeded in getting Harvard Press to refuse to publish it and, after its eventual publication, bore a grudge for several years.

But, as Julio suggested, none of that rises to the level of ‘flawed’. But flaws, sadly, there are. In the 70s, Crick was very outspoken on such contentious topics as eugenics, population control and race. He made suggestions that seem outrageous now (and, presumably, then) such as forced sterilization, social experiments on twins (who would be subject to mandatory separation at birth) and a form of licensing to discourage breeding among the genetically unfit.

I won’t spend too much time on Crick’s flamboyance. Just open the book at any page to read of the parties at his residence, The Golden Helix (at one party in particular, guests were handed a sketchpad and required to provide a sketch of the nude life model in the foyer) or of his reckless yachting adventures or his eccentric choice of friends including one who would habitually use Crick’s name whenever he was arrested (often) or picking up women on foreign beaches (all the time).

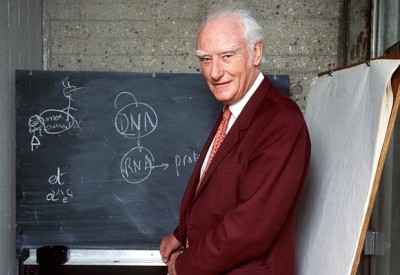

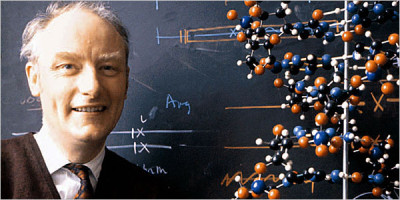

The book is ultimately, of course, about Crick’s genius which seems almost unfathomable. Consider a man who quit his well-paying job to enter academia but could not decide whether to first solve the secret of life or whether to explain the nature of consciousness. With the double helix well-documented and the DNA code cracked Crick still found time, at the age of 60 to start work on the second problem. Sadly, time ran out for Francis Crick in 2004. I am sure he would have cracked that one too if he had only started a little earlier.

One day, when I am rich, I will have a house with a study and on the walls of that study will be the portraits of all my heroes. Francis Crick will be up there with Bob, George, Winston and the others.